Konark

“Here the language of stone surpasses the language of man”

Konark, Odisha

The Konark Wheel

On the shores of the Bay of Bengal, bathed in the rays of the rising sun, is the monumental temple of Konark, a representation of the sun god Surya's chariot escorted by his charioteer Aruna, led by a team of seven horses with 24 wheels bedecked with symbolic designs. Built in the 13th century with Orissa red sandstone (Khandolite) and black granite by King Narasimhadeva I (AD 1238-1264) of the Eastern Ganga dynasty, it is one of India's most famous Brahman sanctuaries. The temple was commissioned by the king to mark his victory over the Muslim invaders and Siva Samantaraya Mahapatra oversaw its construction with 1200 artisans over 12 years. By the end of the 13th century, the Muslims had conquered the whole of the northern India, except Kalinga, where the Hindu rulers deflected their attacks for quite some time. A great fight took place between Tughan Khan ( Nasir-ud-Din Mahmud Shah Tughluq’s, the last sultan of the Tughluq dynasty, General) and he was comprehensively defeated by Narasimhadeva, thus, the Kirti Stambha (victory memorial) was erected, as a symbol of his prestige.

The name Konark comes from the combination of the Sanskrit words Kona (corner or angle) and Arka (the sun) implying the sun and the four corners. The temple is known for its exquisite stone carvings that adorn the facade. Located in the village of Konark, 35 kilometers north of Puri on the coast of the Bay of Bengal, it is the best-known tourist destination in Orissa and has been a World Heritage Site since 1984. The temple was called the Black Pagoda attributed to its dark facade by Europeans who used it to navigate their ships. It is said that the temple could draw ships to the shore due to its magnetic powers. Interestingly the Jagannath Temple was known as the White Pagoda and both temples served as important landmarks for sailors in the Bay of Bengal.

The Konark Sun Temple is one of the finest examples of Brahmin architecture and beliefs, built to honor the Sun God, Arka, the temple complex displays the enormous wealth, talent, and spirituality of the Brahmin in Kalinga. The Sanātana Dharma or Hinduism, is the world's oldest continuously practiced religion, presenting a mixture of the sublime spiritually and the earthly erotic in the Konark Temple. Much of the temple has fallen into rack and ruin but what remains still holds enough charm to captivate. An interpretation of a greater imagination, it has seen empires rise and fall, identities washed away, yet appeals to our sensorium even today.

Located on the eastern shores of the Indian subcontinent, it is an outstanding example of temple architecture and art as revealed in its conception, scale and proportion, and in the sublime narrative strength of its sculptural embellishment. It is an outstanding testimony to the 13th-century kingdom of Kalinga, present day Orrisa, and a monumental example of the personification of divinity, thus forming an invaluable link in the history of the diffusion of the cult of Surya which, originating in Kashmir during the 8th century, finally reached the shores of Eastern India. In this sense, it is directly and materially linked to Brahmanism and tantric belief systems. The Sun Temple is the culmination of Kalingan temple architecture, with all its defining elements in complete and perfect form.

I had the privilege to spending some time at this monument way back in March 2009 and the photos shared here are from that time. This is a story more than a decade in the making although I did do a brief piece in my book in 2011.

A masterpiece of creative genius in both conception and realisation, the temple represents a colossal chariot of the Sun God, with twelve pairs of wheels drawn by seven horses evoking its movement across the heavens. It is embellished with sophisticated and refined iconographical depictions of contemporary life and activities. On the north and south sides are carved 24 wheels, each about 3 meters in diameter, and symbolic motifs referring the cycle of the seasons and the months. Each giant wheel is designed as a Sundial with a diameter of 9 feet and 9 inches with 8 thick and 8 thin spokes. There are various theories regarding the Konark Wheel - some call it the Wheel of Life while others call it the Wheel of Karma. Each wheel is sized the same but the craft work on each is unique. Between the wheels, the plinth of the temple is entirely decorated with reliefs of fantastic lions, musicians and dancers, and erotic groups. These complete the illusionary structure of the temple-chariot.

Two giant lions guard the entrance, each in the act of crushing a war elephant and each elephant, in turn, lies on top of a human body. The temple symbolises the majestic movement of the Sun god. At the entrance of the temple stands a Nata Mandir, where the temple dancers performed in homage to the Sun god. All around the temple, various floral and geometric patterns decorate the walls. Etching and reliefs of human, divine and semi-divine figures in sensuous poses also decorate the walls. Couples pose in a variety of amorous poses derived from the Kama Sutra. Parts of the temple now stand in ruins, with a a collection of its sculptures removed to the Sun Temple Museum run by the Archaeological Survey of India.

The great Bengali poet, Rabindranath Tagore, wrote of Konark:

“Here the language of stone surpasses the language of man.“

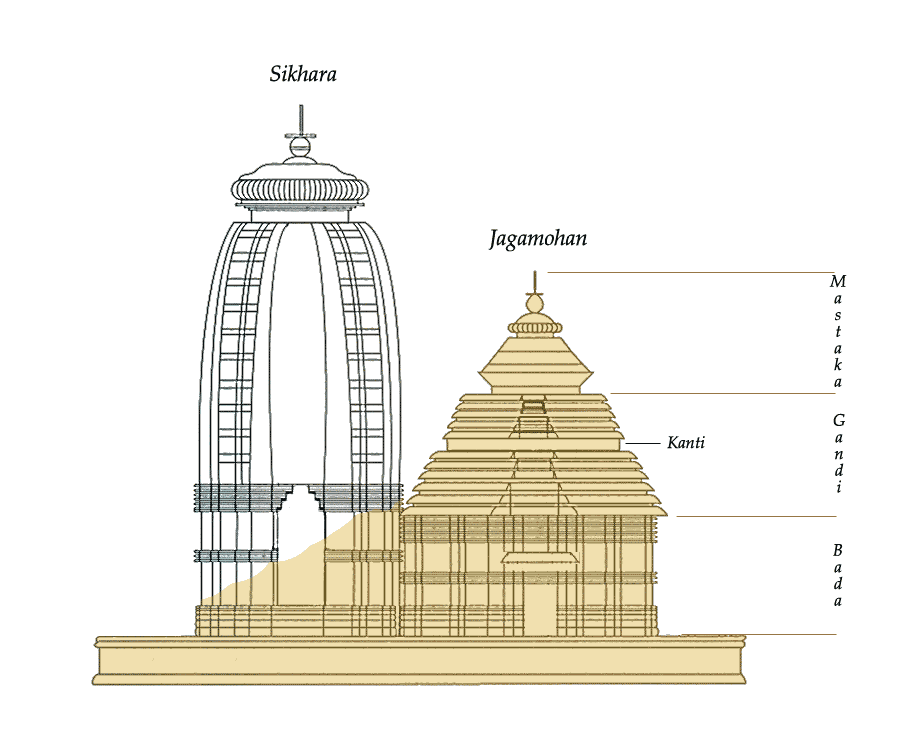

The temple follows the Kalinga or Orissa style of architecture, which is a subset of the nagara style of Hindu temple architecture. The Orissa style is believed to showcase the nagara style in all its purity. The nagara was among the three styles of Hindu temple architecture in India and prevailed in northern India, while in the south, the dravida style predominated and in central and eastern India, it was the vesara style. These styles can be distinguished by how features such as the ground plan and the elevation were represented visually.

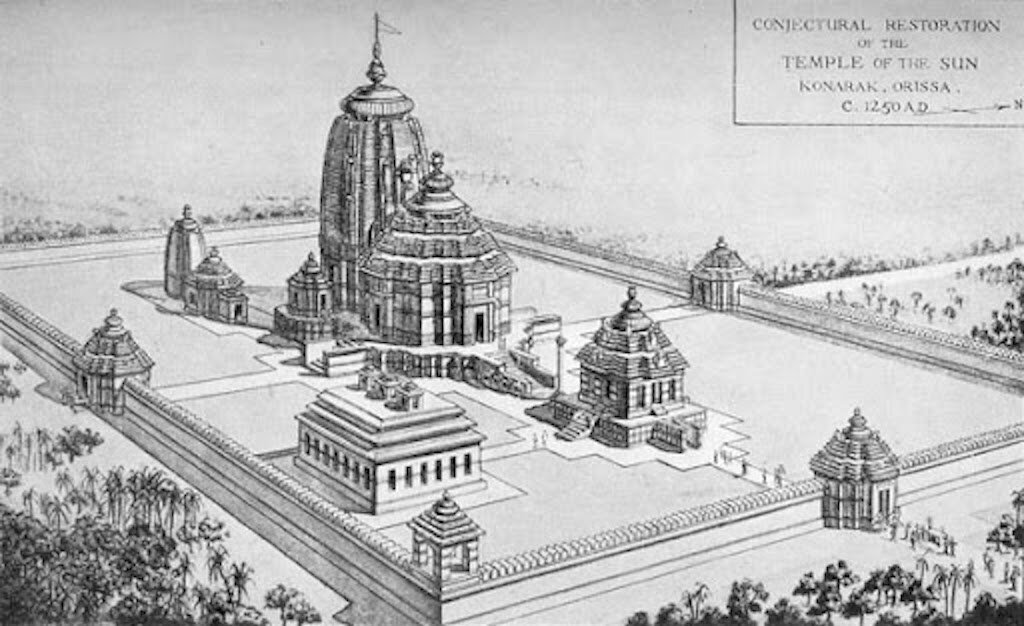

Left: Conjectural Reconstruction of Konark Temple by Percy Brown (from the "Indian Architecture" by Percy Brown, 1942)

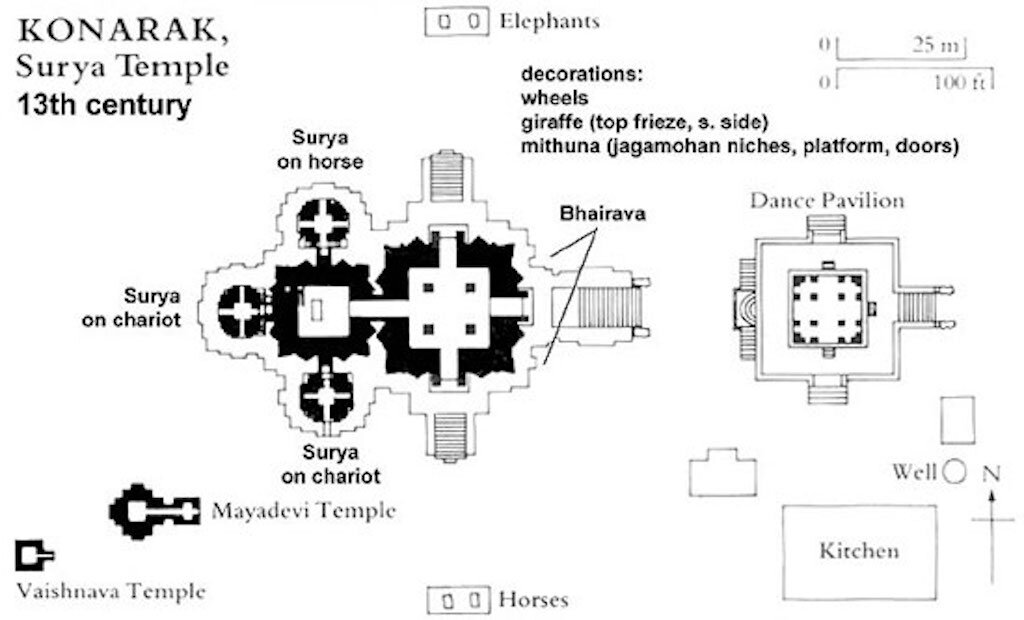

Right: The Konark Temple Layout

The nagara style is characterized by a square ground plan, containing a sanctuary and a audience hall (mandapa). In terms of elevation, there is a huge curvilinear tower (shikhara), inclining inwards and capped. Despite the fact that Odisha lies in the eastern region, the nagara style was adopted. This could be due to the fact that since King Anantavarman Chodaganga’s domains included many areas in northern India as well, the style prevalent there decisively impacted the architectural plans of the temples that were about to be built in Odisha by the king. Once adopted, the same tradition was continued by his successors too, and with time, many additions were made.

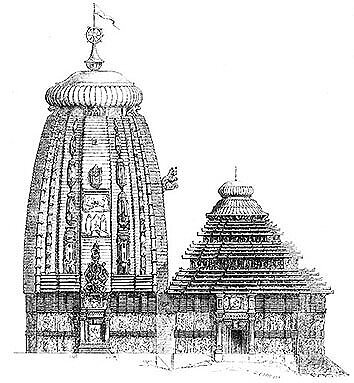

Like many Indian temples, the Konark Sun Temple comprises several distinct and organised spatial units. The vimana (principal sanctuary) was surmounted by a huge 230 feet high tower with a shikhara (crowning cap), razed in the 19th century. To the east, the 128 ft high jagamohana (audience hall) dominates the ruins with its pyramidal mass. Farther to the east, the natmandir (dance hall), today unroofed, rises on a high platform. Dancing and offering both were probably done in the same building. In the Orissan architecture this type of temple is known as pancha-ratha-dekha deul, as each of its facades are broken by five small projections to produce an effect of light and shade on the surface and also to create an impression of one continuous vertical line, called Rekha. Various subsidiary structures are still to be found within the enclosed area of the rectangular wall, which is punctuated by gates and towers. The Sun Temple is an exceptional testimony, in physical form, to the 13th-century Hindu Kingdom of Kalinga, under the reign of Narasimha Deva I (AD 1238-1264).

The Jagamohana and the pillared bhoga mandapa (refectory hall), also known as the nata mandapa (dancing hall)

The magnificent vimana and its shikhara have been lost with time. Today, only the jagamohana and the pillared bhoga mandapa (refectory hall), also known as the nata mandapa (dancing hall) owing to the numerous sculptures of dancers and musicians on its walls and pillars, in front, remain. The most popular theory about the fall of the Konark temple rests with the Kalapahad. According to the history of Kalinga, Kalapahad invaded Orissa in 1508 C.E.. He destroyed the Konark temple, as well as a number of Hindu temples in the region. The Madala Panji of the Jagannath temple describes how Kalapahad attacked Kalinga in 1568. Though it would be impossible to destroy the Sun temple of Konark, given its stone walls which are 20 to 25 feet thick, Kalapahad somehow managed to displace the Dadhinauti (Arch stone) and thus weakened the temple leading to its collapse. He also broke most of the images as well as side temples of Konark and eventually due to the displaced Dadhinauti, the temple gradually collapsed and the roof of the Mukasala suffered damage from the collapse.

The Legends of Konark

Konark is mentioned in ancient Hindu texts having mythological significance like the Puranas and it was believed to be the most sacred place for the worship of Surya in the entire region. In gratitude for healing his skin ailment, Samba, one of Lord Krishna’s many sons, erected a temple in the honour of Surya. He even brought some Magi (sun-worshippers) from Persia, as the local Brahmanas refused to worship Surya’s image. This story was associated with a sun temple in north-western India, but was shifted to Konark in order 'to enhance the sanctity of the new centre by making it the site of Samba’s original temple'. Konark, over time, had emerged as an important site for sun worship and hence, a mythological background was considered necessary to increase its importance for devotees.

There is a legend about the deity of Surya, made of chlorite stone, that supposedly was floating mid-air. Some say that the Idol was made of a material with iron content. Legends describe a lodestone on the top of the Sun temple. Due to its magnetic effects, vessels passing through the Konark sea felt drawn to it, resulting in heavy damage. Other legends state that magnetic effects of the lodestone disturbed ships' compasses so that they malfunctioned. To save their shipping, the Muslim voyagers took away the lodestone, which acted as the central stone, keeping all the stones of the temple wall in balance. Due to its displacement, the temple walls lost their balance and eventually fell down. But records of that occurrence, or of such a powerful lodestone at Konark, have never been found.

The same lodestone also helped align the Idol of the Sun God in such a way that the first ray would fall and reflect from the diamond placed at the crown of the Sun God. It is never proven as the entire main temple is in ruins with no indication of its glorious past. Even in the sanctuary, the holiest spot in any Hindu temple, sculptures in niches depict secular themes; the themes of the niches inside the pavilions, with a single exception where a preacher-like figure is seen seated in meditation, centre on the life of a king in the palace.

Its scale, refinement and conception represent the strength and stability of the Ganga Empire as well as the value systems of the historic milieu. Its aesthetical and visually overwhelming sculptural narratives are today an invaluable window into the religious, political, social and secular life of the people of that period. The Sun Temple is directly associated with the idea and belief of the personification of the Sun God, which is adumbrated in the Vedas and classical texts. The Sun is personified as a divine being with a history, ancestry, family, wives and progeny, and as such, plays a very prominent role in the myths and legends of creation.

The 128 feet high Jagamohana (audience hall)

Construction

Three kinds of stone were used in the temple’s construction - chlorite, laterite and khondalite. Khondalite was used throughout the monument while chlorite was restricted to door frames and to a few sculptures, while laterite was used in the foundation, the (invisible) core of the platform and in the staircases. None of these stones was available near the site and material was brought from long distances. The stone blocks were lifted possibly by the means of pulleys, wooden wheels or rollers and then set into place. The fitting and finishing were done so expertly that the joints could not be seen.

A unique artistic achievement, the temple has raised up those lovely legends which are affiliated everywhere with absolute works of art: its construction caused the mobilisation of 1,200 workers for 12 years. The architect, Bisu Moharana, having left his birthplace to devote himself to his work, became the father of a son while he was away. This son, Dharmapada, in his turn, became part of the workshop and after having constructed the cupola of the temple, which his father was unable to complete, sacrificed himself by jumping from the cupola he had constructed.

The Sun Temple’s authenticity of form and design is maintained in full through the surviving edifices, their placement within the complex, structures and the integral link of sculpture to architecture. The various attributes of the Sun Temple, including its structures, sculptures, ornamentation and narratives, are maintained in their original forms and material. Its setting and location are maintained in their original form, near the shore of the Bay of Bengal. In preserving the attributes as stated, the Sun Temple, Konark repeatedly evokes the strong spirit and feeling associated with the structure, which is manifested today in the living cultural practices related to this property, such as the Chandrabhanga festival.

Mayadevi Temple

Discovered in 1909 during the excavations, it lies to the west of the Sun temple. An important temple in the complex this is dedicated to Mayadevi - the wife of Surya, the temple is older than the Sun temple built around the 11th century. Its sanctum houses a Nataraja, and other chambers of the temple have idols of Surya with Vishnu, Vayu, Agni. The temple was considered by some as another temple made to worship sun god but a few believe that it was dedicated to the wife of Surya.

Sculptures

During Narasimhadeva’s reign, Eastern Ganga art reached its zenith and at Konark the sculptures display these heights; 'Nowhere is this era of Kalinga sculpture better represented than in the gigantic and miniature carvings which decorate the jagamohana. Every bit of space available has been covered by the sculptors and with what appears as an endless variety of themes, with figures indulging in song and dance and in activities related to kama (Sanskrit: “desires and sensual enjoyment”). There are also depictions of mythical beings, birds and animals, besides floral and geometrical motifs. The designs were carved after the stones had been set into place.

Panels represent King Narasimhadeva in various roles - as a scholar reviewing literary works being presented to him by poets, as enjoying himself on a swing in his palace, as a great archer, and as a deeply religious devotee. These are made from pink and green khondalite (these panels can also be viewed at the National Museum, New Delhi). These depictions dominate to such an extent that it appears that 'the sculptors were so busy highlighting the myriad facets of royal life that they had very little scope to record the daily life of the common man'.

Kalinga came under Muslim control in 1568 C.E., resulting in frequent attempts to destroy the Hindu temples. The Pandas of Puri, to save the sanctity of the Puri temple, took away the Lord Jagannath from the Srimandir and kept the image in a secret place. Similarly, the Pandas of Konark removed the presiding deity of the Sun temple and buried it under the sand for years. Later, reports say the image had been removed to Puri and kept in the temple of Indra, in the compound of the Puri Jagannath temple. According to some, the Puja image of the Konark temple remains to be discovered. But others hold the view that the Sun image now kept in the National Museum of Delhi constitutes the presiding deity of the Konark Sun temple.

The Sun worship in the Konark temple, including pilgrimages, ended with the removal of the image from the temple. The port at Konark closed due to pirate attacks. Konark's renown for Sun worship was matched by its fame in commercial activities, but after the Sun Temple ceased to attract the faithful, Konark became deserted and was left to disappear into the dense forests for years.

By the end of the eighteenth century, Konark had lost its glory, turning into to a dense forest, full of sand, filled with wild animals and the abode of pirates. Reportedly, even the locals feared to go to Konark in broad daylight.

Today this World Heritage Site is well connected to all major parts of India by road, rail and air and easily accessed by taxis from the closest ports for each.

Related Posts